Actually, this is my mom’s story, and I know she would want me to share it with you. She was an amazing lady and she is the one responsible for my healthy lifestyle. She taught me almost everything I know, having learned it herself at great cost, and gave me a strong foundation on which to build. She is no longer living on the earth she worked hard to steward well, but I know she is still with me in spirit, cheering me on as I teach others what she taught me. Thanks, Mom, for an invaluable legacy!*

*Disclaimer: The preceding is the author’s account of a true story. No statements on this page are intended to advise or influence the reader in the area of personal health. When it comes to health matters, it is the reader’s responsibility to do the necessary research and to seek the help of a qualified, licensed healthcare professional.

“For the first time in the history of the world, every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals, from the moment of conception until death.”

— Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring (1962)

My Mother’s Postwar Battle

Here I am, sitting at my computer, just as my mother sat at her typewriter over sixty years ago, when she was bent on saving her family from a toxic avalanche. In the name of progress, the earth was being smothered with the inventions of modern science. It was a time when only a few courageous voices cried out about the gradual poisoning of our planet. My mother, Ruth Morgan, was among those few.

The devastating trend began back in the mid-nineteen-forties. During the Second World War, scientists experimented with and developed many chemical substances for the purpose of warfare, as a result of which the chemical industry entered the ranks of big business. When the war was drawing to a close, these companies had to find a new outlet for their products–one that would enable them to maintain the high profits they had established and enjoyed. They turned their attention to the newly restored domestic scene and the idea that chemicals could make life easier and more pleasant, almost picture perfect for the average man and his family.

The devastating trend began back in the mid-nineteen-forties. During the Second World War, scientists experimented with and developed many chemical substances for the purpose of warfare, as a result of which the chemical industry entered the ranks of big business. When the war was drawing to a close, these companies had to find a new outlet for their products–one that would enable them to maintain the high profits they had established and enjoyed. They turned their attention to the newly restored domestic scene and the idea that chemicals could make life easier and more pleasant, almost picture perfect for the average man and his family.

There was soon a host of chemicals available for use as insecticides, household cleaners, air fresheners, toiletries, cosmetics, and as food additives and preservatives. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), entrusted with the welfare of the American citizen, at that time placed no restriction on the chemicals that were flooding the market. Synthetic chemicals were being touted as the miracle cure for the challenges of nature and daily life. Everything was so much easier and more convenient for the new generation of mothers, raising their children in the progressive and prosperous postwar era, but, for my mother, life was becoming a nightmarish struggle.

A Promising Career Crumbles

When the war ended, Mom was twenty-one years old. She was living with her parents in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and her life was devoted to a promising operatic career. Since the age of sixteen, she had dedicated her time and energy to developing her beautiful contralto voice and making plans for her future.

When the war ended, Mom was twenty-one years old. She was living with her parents in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and her life was devoted to a promising operatic career. Since the age of sixteen, she had dedicated her time and energy to developing her beautiful contralto voice and making plans for her future. At the age of nineteen, she continued her studies at the Julliard School in New York City and, at home, became a founding member of the Pittsburgh Opera Company, singing, among other roles, the leads in Bizet’s Carmen and Saint-Saens’ Samson et Dalilah. At this point her sights were set on the Metropolitan Opera, but before she could reach her goal, her budding career began to crumble under the pressure of sudden and mysterious health problems.

At the age of nineteen, she continued her studies at the Julliard School in New York City and, at home, became a founding member of the Pittsburgh Opera Company, singing, among other roles, the leads in Bizet’s Carmen and Saint-Saens’ Samson et Dalilah. At this point her sights were set on the Metropolitan Opera, but before she could reach her goal, her budding career began to crumble under the pressure of sudden and mysterious health problems.

There was soon a host of chemicals available for use as insecticides, household cleaners, air fresheners, toiletries, cosmetics, and as food additives and preservatives. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), entrusted with the welfare of the American citizen, at that time placed no restriction on the chemicals that were flooding the market. Synthetic chemicals were being touted as the miracle cure for the challenges of nature and daily life. Everything was so much easier and more convenient for the new generation of mothers, raising their children in the progressive and prosperous postwar era, but, for my mother, life was becoming a nightmarish struggle.

Marriage, Children, & Devastating Loss

Mom met Dad in 1949, when she reluctantly agreed to a blind date. Dad had served as a medic in Berlin, in the Army of Occupation, after which he enrolled in the University of Pittsburgh under the G.I. Bill, graduating with a Bachelor’s degree in accounting. Dad was immediately smitten and determined to win Mom’s hand, and in June of 1950, Mom became Mrs. Hillard Morgan. With a new wife and the intention of raising a family, Dad returned to the university and earned his Master’s degree in retailing, after which my parents relocated to Dayton, Ohio, where there were abundant career opportunities for young WWII veterans. At the age of twenty-eight, Dad became a manager at the local Beerman’s, at that time a rapidly growing department store chain in the Midwest.

determined to win Mom’s hand, and in June of 1950, Mom became Mrs. Hillard Morgan. With a new wife and the intention of raising a family, Dad returned to the university and earned his Master’s degree in retailing, after which my parents relocated to Dayton, Ohio, where there were abundant career opportunities for young WWII veterans. At the age of twenty-eight, Dad became a manager at the local Beerman’s, at that time a rapidly growing department store chain in the Midwest.

In 1952, on the eve of Thanksgiving Day, my older sister Alicia was born. Mom’s health problems persisted, and now she had an infant daughter who was having negative physical reactions to her baby food. Mom continued to seek medical assistance to no avail; and it was around this time that she began hearing the term psychosomatic–a harbinger of the ridicule to which she would soon be frequently subjected in her search for help.

When Alicia was sixteen months old, Mom became pregnant for a second time. On a lovely spring day, in the third month of that pregnancy, my parents drove out to farm country to buy fresh produce. As they traveled along a rural road, lined with fruit trees, they encountered a large tanker truck. There were hoses connected to the tank, with which workmen were spraying the trees. Dad unwittingly drove the car right through a cloud of DDT, a dangerous and very widely used pesticide that has since been outlawed. Mom immediately became extremely ill with an onslaught of the many symptoms to which she had become accustomed, but this time they were more severe than ever and struck simultaneously.

Her doctor later assured her that she was fine and that her unborn child had not been harmed. She carried full term, though a week before delivery she ceased to feel any movement in the womb, and, over the New Year’s weekend, she gave birth to a badly deformed, stillborn boy. My parents had lost their son, but my mother had gained the realization of what had been destroying the quality of her life.

My parents had lost their son, but my mother had gained the realization of what had been destroying the quality of her life.

For years after that tragic loss, Mom’s days were filled with the quest for information about modern farming practices and the use of synthetic substances on and in food products. She wanted to know what she was putting in her child’s mouth; she wanted to know what she was feeding her husband and herself. She wanted her health back, and for the first time she saw a glimmer of hope. Ambitious though she was, she soon found that information was not forthcoming from government agencies, doctors were ignorant on the subject, and the average private citizen simply did not want to know. A few more years passed–years that brought my birth and further painful struggles–before she finally began to get the answers to her questions and the pieces of the puzzle began to fit together.

Being very loving and nurturing by nature–very much the archetypal mother, Mom scorned the popular trend away from breast-feeding and nursed her children. I was a happy, healthy baby with good sleeping habits until solid foods were introduced into my diet, at which time a red patch began to form on my cheek. The pediatrician was unable to make a diagnosis, but nevertheless he prescribed cortisone to be applied externally. Mom followed his advice and saw no improvement.

When I was fourteen months old, Dad accepted a position with a company in Boston and we settled in the suburb of Newton, Massachusetts. My skin condition still persisted, it began to grow worse and spread to other parts of my body. Before long my cheeks and the backs of my hands had the appearance of raw flesh. As the months passed, my sleeping habits deteriorated and I was seized almost every night with agonizing cramps. Again, the doctor’s prescription (this time it was paregoric) brought no relief. Mom, now pregnant with my sister Michele, spent nights walking the floor with me, trying desperately to ease my pain and quiet my screams.

These were very trying times for my parents. They were already dealing with all the usual challenges stresses and necessary adjustments involved in moving, with two children, to a new home in another state. Within less than a year after the move my sister Michele was born and then, after only a year at his job, Dad was let go due to the company’s financial problems and inability to meet their payroll. This development took a toll on our family, but thankfully the period of unemployment was relatively short lived. Dad soon secured a procurement position with the Federal government, negotiating weapons contracts for the United States Air Force. It was a demanding job that required frequent trips to the Pentagon, as well as periodic trips out of state, and sometimes abroad.

Mom continued to struggle with the challenges at home. She now had a new baby girl to care for, while her own symptoms continued to plague her and my condition was still showing no sign of improvement. With the loss of their son a few years earlier, Mom had learned of the dangerous pesticides being used in the cultivation of commercial produce. Now, because of her determination to stop my suffering, she was about to learn a lot more.

At this point, she was convinced that I was reacting to something in the foods. She observed that my symptoms repeatedly occurred after she fed me trimmed lamb chops, beef or chicken. Clearly, they were triggered by something common to the meats, but what could it be? She renewed her efforts to obtain information from government agencies Once again she wrote letters and made phone calls, only to be met with endless referrals leading nowhere. Drained and frustrated, filled with a sense of helplessness, and not knowing what further action to take, she said a prayer.

Discovering the Facts

Mom’s prayer was answered when, on her way to a department store in a neighboring town, she noticed a small health food store and stopped in to see what it offered. Like most health food stores in those days, this one dealt mainly in vitamins and food supplements, and carried little else. What she did find, however, was information about local lectures by experts in nutrition and natural farming methods. She attended one of those lectures and was there referred to a book that triggered a major turning point in our lives.

Mom’s prayer was answered when, on her way to a department store in a neighboring town, she noticed a small health food store and stopped in to see what it offered. Like most health food stores in those days, this one dealt mainly in vitamins and food supplements, and carried little else. What she did find, however, was information about local lectures by experts in nutrition and natural farming methods. She attended one of those lectures and was there referred to a book that triggered a major turning point in our lives.

The Poisons in Your Food was an unprecedented exposé, in which the author, journalist William Longgood, had disclosed the whole truth about what post-war America was eating. Mom soon found that this book was not stocked by any of the local retailers and she had to order it directly from the publisher. When she finally had it in her hands, she immediately read it cover to cover and was overcome with both horror and relief: She was horrified to learn of the extent of the dangers our society was facing, and relieved to be in possession of the facts at last.

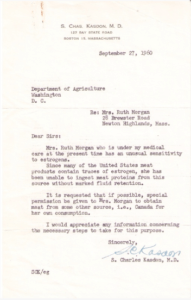

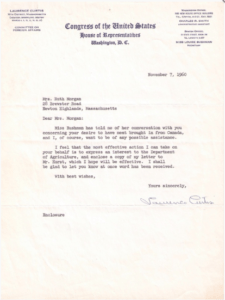

From her recently acquired book, she also learned that in Canada, the use of hormones in agriculture had been found to be dangerous to the health of the consumer, and had therefore been outlawed by the Canadian government. After months of perseverance in the face of bureaucratic resistance, she obtained permission from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to import meat from Canada as a private citizen. She then succeeded in contacting a butcher in Quebec, who was happy to oblige by packing large boxes of fresh meat with dry ice and shipping them to Boston on a regular basis. Meats were back in our diet and this tie we were thriving.

Toxic Food, Toxic Environment

Through her new contacts in the small but dedicated organic foods movement and her own extensive research, Mom had soon compiled a vast amount of information, including sources of organic food products. Within a few years we were receiving fresh produce weekly by air freight from California. We received large blocks of delicious cheddar cheese from an old organic dairy farm in the Midwest. Canned goods, peanut butter, honey and grains arrived by truck, and eggs (laid by organically fed, free range hens) by parcel post, all from a farm in Pennsylvania. Walnut Acres, in Penns Creek, Pennsylvania, was one of the oldest organic farms in the United States and, at that time, offered the only organic foods mail-order catalog in the country.

Canned goods, peanut butter, honey and grains arrived by truck, and eggs (laid by organically fed, free range hens) by parcel post, all from a farm in Pennsylvania. Walnut Acres, in Penns Creek, Pennsylvania, was one of the oldest organic farms in the United States and, at that time, offered the only organic foods mail-order catalog in the country.

All of these organically raised foods were far more expensive than their pesticide- and additive-laden counterparts, then available at the local supermarkets, and with all of the freight bills Dad had no small burden to support his family. To minimize expenses, he stubbornly insisted on continuing to eat the commercial foods himself, arguing that he had never demonstrated Mom’s extreme sensitivity to the the chemicals. Dad never did fully embrace the organic lifestyle for himself, but he did understand and appreciate his family’s critical need to adhere to it. He supported, without question, Mom’s choices and tireless efforts to do whatever was necessary for herself and their children, even though he never assumed an active role in that area.

When I was about two-and-a-half years old, not long after our transition to an organic diet, a serious incident occurred, which demonstrated the extent of the pervasive threat under which we were living. It was a sunny autumn day and Mom had taken me outside in our front yard. She got into conversation with a neighbor and took her eyes off of me for no more than a second or two, at which point I took a playful dive into a large and tempting mound of leaves. At that time, the city had begun routinely spraying the trees with DDT. Alarmed at the possible effects on me, Mom quickly pulled me out of the leaves, rushed me into the house and carried me straight to the bathtub. She bathed me thoroughly from head to toe, but the damage had been done and the next morning I awoke with my eyes swollen shut. When the swelling did not appear to be going down, my parents took me to Massachusetts Eye and Ear Hospital, where the doctors kept me overnight for observation. They were not able to immediately relieve or diagnose my condition and went so far as to conjecture that blindness was a possibility.

The doctors were considering different types of treatment for me, to which my mother did not wish to submit. Instead, she sneaked a large supply of vitamin C into my hospital room and gave me massive doses during the night, to flush out the toxins. The next morning, my eyes were back to normal. I was released from the hospital and the doctors were completely dumbfounded. Mom soon read about an epidemic of the same condition occurring among small children all over the Boston area. At that time the condition had still not been diagnosed and I don’t know if the mystery was ever solved or the symptoms successfully treated by the medical establishment.

It was clear that changing our diets solved only part of the problem. Mom still had to be concerned with protecting herself and her children, as much as possible, from the airborne contaminants. Toxic chemicals were used in the cleaning and maintenance of public buildings, including the schools we attended. DDT was sprayed seasonally in residential areas all over the country. In those days many people burned the fallen leaves as a regular part of their yard maintenance–leaves that were covered with the dangerous chemical. Every autumn, up and down the residential streets of our beautiful community, clouds of toxic smoke were daily released into the air. Our ability to walk home from school and play outdoors was restricted in the autumn by the burning leaves and in the spring by the mass spraying of DDT. Whenever we were outdoors, seeing dead birds on the ground was commonplace, and continued to be a daily occurrence until DDT was outlawed.

From Organic Farm to Suburban Table

Although life was extremely challenging for us in those days, the practice of eating strictly organic foods, and being environmentally aware and responsible, was something about which I always felt very positive and, just like Mom, deeply passionate. Despite the struggles, I recall that aspect of our lives with much more pleasure than pain.

For years, on many spring, summer, and early autumn weekends, we would load up the back of our station wagon with a couple of large ice chests and the whole family, including our beloved German shepherd, Trina, would set off on road trips throughout the Northeast, visiting many of the organic farms Mom had discovered through her extensive research. We would always come home from those trips happily exhausted, with a cornucopia of beautiful fruits and vegetables, fresh eggs, cheese, meats, and other organic goodies to enjoy.

Autumn visits to one particular farm in Red Hook, New York, in Dutchess County, were especially memorable. Mom had developed a warm relationship with Y. K. and Helen Smith, the couple who owned and ran the farm, so the visits became a very pleasant social occasion, as well. Y. K Smith, a graduate of Tulane University, came from a very distinguished family. He was the son of William Smith, textbook author and Professor of Mathematics and Philosophy at Tulane. Y. K.’s elder brother Bill had gone into public service and written some speeches for President Harry Truman.Y. K. had once worked as a publicist in Chicago and went on to become a highly successful advertising executive in New Your City.

As a young man, Y.K. counted among his friends and acquaintances many illustrious individuals from various walks of life. One of these was author Ernest Hemingway, who was well acquainted with the Smith family from childhood. In 1920, when working as a journalist, Hemingway had lodged in Y. K.’s Chicago apartment for an extended period of time, and it was through the Smith family that Hemingway met his first wife. While Hemingway went on to great renown as a Nobel Prize winning author and life in the fast lane, Y. K. ultimately gave up his own sophisticated lifestyle in the big city to become an organic farmer.

We were always invited to arrive early at the Smith farm, to spend the day picking apples in their beautiful apple orchard, and to stay to a delectable organic dinner. The large rustic farmhouse was warm and inviting and the food–entirely homegrown and homemade, including freshly baked whole grain breads and freshly churned raw butter–was healthy, delicious and plentiful. The meal was always accompanied by lively, philosophical and very enlightening conversation, and, even as a young child, I listened with interest.

It was, of course, highly unconventional for a suburbanite family in the 1960s to set foot on the actual land on which their food was raised and to break bread with the farmers. So many of those involved in organic farming at that time were, like Mom, well educated, intellectual, creative and spiritual individuals. They shared a deep and abiding belief in giving back to the land, and a heart-held vision of a healthy and sustainable future for our planet and its inhabitants. Mom was always grateful for the opportunity to expose her children to the knowledge and insight of these extraordinary people.

Maintaining a Balance

Mom’s top priority was keeping her family physically healthy, but she was keenly aware of the social implications of our having such unusual special needs and was also determined to protect us as much as possible from any emotional damage. Michele was just a toddler and I was still a preschooler at the time mom was taking our family through all of the dietary and lifestyle changes. Michele has no memory of our household prior to the organic years, but I have many very clear memories of those times and of the transitional period that followed.

Some of my favorite foods began disappearing from our pantry and refrigerator, one by one. Often, during this period, I would ask Mom for something she had customarily fed me in the past and she would tell me that it was all gone, that she wouldn’t be buying it anymore. I remember when Mom canceled our regular delivery from the local dairy. The milkman never again came to our backdoor and I missed looking for those glass bottles on the back stoop every morning. All of these changes were strange for me at first, but Mom explained it all in such a way that even at my tender age I was able to understand and adjust.

In those days, more than a half-century ago, people thought very differently about diet than they do today In the Twenty-first Century, special dietary needs among adults and children are commonplace. There is a long list of foods and food components, one or more of which many people have been medically advised, for various health reasons, not to consume. Included on that list are gluten, lactose, peanuts, beef, sodium and sugars, along with many more items. Many people are vegetarians and some are vegans. Some avoid carbohydrates and some minimize their protein consumption.

Many people are now very anxious to stay away from commonly used ingredients, such as trans fats, high fructose corn syrup, monosodium glutamate, and several others that are now widely known to cause serious health problems. The list of currently widespread dietary constraints–whether due to medical issues or personal choice–goes on and on. Today, a person requesting consideration for a particular dietary need, even at a catered affair, will not likely cause a raised eyebrow, a double-take, or even a momentary look of consternation or confusion.

Not so back in the 1960s, when dietary restrictions were thought of mainly in relation to those with heart disease or diabetes. Food labels were lacking a lot of information that is now required by law and people generally did not bother to read them anyway. With total trust in the FDA, the American population enthusiastically embraced Madison Avenue’s propaganda. Just as cigarette smoking had previously been promoted as having wonderful health benefits, refined white sugar (stripped of its natural mineral content and chlorine bleached) was now being advertised as a great dietary choice to boost energy levels through the day.

Urban and suburban families consumed a diet of chemically treated, adulterated, denatured foods. Virtually all parents insisted their children drink milk, many having already switched from milk produced at local dairies to supermarket milk from factory farms; and they relied on cafeteria lunches, never questioning the quality or nutritional value of the meals. anyone who deviated from the norm was at high risk of being looked upon with suspicion or even condemnation.

By the time Michele and I were both in school, we were very firmly and confidently established in our organic way of life. Mom fed us strictly organic foods at home and always prepared lunches for us to take to school. Because our lunches looked completely different from those of our classmates, we were often bombarded with comments and questions from them, and even sometimes from our teachers.

Our sandwiches were made on home-baked, hand-sliced whole grain or sprouted grain breads rather than on the bleached, synthetically enriched, machine-sliced, white bread the other children were eating. Our peanut butter was darker, because it had nothing in it but peanuts with their skins. Our cheese was made in small artisan batches and hand sliced from the wheel or block, while theirs was processed, artificially colored, and molded into ‘slices’. We had dried fruit and raw peanuts, pumpkin seeds and sunflower seeds for snacks instead of chips or prepackaged crackers with processed cheese spread. Our desserts were baked from scratch with whole wheat flour and honey, and looked nothing like our classmates’ packaged chocolate snack cakes.

Still, our lifestyle never became the major social issue for us that it might have been. With a little coaching from Mom in the beginning, we had quickly learned how to field all the comments and questions with relative ease. Being different from other people didn’t faze us at all and we were happy to enlighten our friends, their parents, and our teachers on what was then the little known subject of organic foods. To ensure that we wouldn’t grow up feeling completely isolated or excluded, Mom allowed us, individually and as a family, to accept social invitations that included meals and refreshments. We also occasionally went out for restaurant dinners when relatives and friends visited from out of town, albeit with strict instructions from Mom as to what we were and were not allowed to order from the menu.

Whenever my sisters and I had our friends over, as well as for our wonderful birthday parties, Mom always ordered a beautifully decorated cake from a local bakery and prepared commercial foods that would be familiar and acceptable to the other children. It wasn’t always easy to deal with the physical after effects of those occasional departures from the organic straight and narrow, but for the most part they were minimal and temporary, and we did succeed in avoiding much of the stigma and emotional damage about which Mom had been so concerned.

Alicia, however, was a very different story. She was six years old when our family relocated from Ohio to Massachusetts and she grieved for the home, the school, and the friends she had left behind. The social climate in Dayton had been friendly, open, relaxed and easygoing, while in Newton it was rather cold, aggressive, fiercely competitive, and ultra high-pressure. So while Alicia was already struggling to fit in, in her new surroundings, the fundamental changes taking place at home were compounding the issue.

Throughout her childhood and adolescence, Alicia continued to feel uncomfortable with our family’s lifestyle and embarrassed to appear so different from everyone around her. As her increasing age brought with it greater freedom, she took every opportunity to stray from the organic diet Mom had fought so hard to provide for us.

Mom had done all she could to help us understand, from an early age, the seriousness of our environmental sensitivities and the importance of maintaining an organic lifestyle. She also tried to instill in us a concern, beyond our own personal needs for the environment and the future of our planet. She had taught us well and believed that we would all fully embrace both the organic way of life and the environmental cause, in our own right, as we grew into adulthood. It deeply distressed her to witness the choices her firstborn was making and, over the ensuing years, to see the detrimental effects those choices had on Alicia’s health.

By the time Alicia came of age, she had turned her back completely on her organic upbringing. In an effort to fit in with the mainstream, she did everything in her power to conceal her background from the world, ultimately marrying and raising her own children in an atmosphere of, at worst, diametric opposition, and, at best complete indifference, to almost everything for which our mother stood.

Tough Choices

Mom made one attempt at growing her own food. Just before I started kindergarten, my parents purchased a house on an acre of land, on which Mom soon planted a very large organic garden. This beautiful garden kept us well fed with wonderful fruits and vegetables, but not for long. A few yards from our garden, at the edge of our property, stood a children’s play gym, belonging to our next-door neighbors. The land began to slope sharply downhill at their property line, so my parents had graciously consented to let them use a small section of our land.

After our planting had been completed for a third season, the same neighbors, without notifying my parents, had the city spray one of their trees that stood near the play gym. Like most people at that time, they had no concern about the dangers of DDT, but they were very concerned about caterpillars falling on their two little girls. The spraying was done towards our property and the poison was carried by the wind. Our garden was no longer organic, the soil was rendered useless to us, and we had to keep our windows closed for weeks.

An organic farm of our own would have seemed a practical answer to our needs, but for two reasons. First, Dad possessed neither the knowledge nor the inclination, where farming was concerned, nor did he have Mom’s adventurous spirit. Second, Mom was now regaining her health, but, although she was eventually able to sing again (to the great delight of her family!), her career in music was gone forever and her only consolation was the dreams she cherished for her musically gifted children. She could not imagine how we would be able to pursue our music studies and related activities while growing up on a farm, far from the cultural advantages of the big city.

So my sisters and I were brought up amid the raised eyebrows, glassy-eyed stares, whispers, occasional derisive comments, and generally unsympathetic attitude of those in our well-educated and affluent community, who witnessed or heard of our unusual lifestyle. Mom wanted to share with other mothers the facts she had learned from painful experience, but she was so far ahead of most of her generation. I recall the pathetic response of one woman whose daughter–a classmate of mine–was displaying physical symptoms that were all too familiar to Mom, and had been undergoing conventional medical treatment without any success. “Please don’t tell me anymore, Ruth,” the distraught woman pleaded, “because then I’ll have to do something about it!”

Furthering the Cause

In the early 1970s, when a greater environmental consciousness gradually began to emerge, Mom organized and ran a large food co-op, in which Michele and I often helped out after school. Contrary to the commonly held belief that organic food–often categorized at that time as “health foods”–was just for hippies, active members of Mom’s co-op included Harvard University professors and other academics; the wife of the music critic for the Boston Globe; and the wife of a prominent cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital–a local celebrity in her own right, with a popular, long-running exercise show on Boston’s PBS affiliate.

“health foods”–was just for hippies, active members of Mom’s co-op included Harvard University professors and other academics; the wife of the music critic for the Boston Globe; and the wife of a prominent cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital–a local celebrity in her own right, with a popular, long-running exercise show on Boston’s PBS affiliate.

Mom also found satisfaction in working as a consultant and counselor to families and individuals who were anxious to make a transition to a healthier lifestyle. As her reputation spread, she was sought after by the respective owners of several fledgling natural foods markets in our local area, in their search for product sources. The first to contact Mom were the owners of Erewhon Natural Foods, who were getting ready to open their first store in 1968. The owners of Bread & Circus contacted Mom in the early 1970s.

Mom’s years of tireless effort, researching and sourcing organic foods to feed her own family, made it possible for these businesses to get off to a strong start and to continue to grow and thrive, ultimately feeding countless families throughout Greater Boston. Erewhon soon opened a second store in Cambridge. Now there are four Erewhon locations in the Los Angeles area. Bread & Circus went on to open several more stores and ultimately sold out to Whole Foods in the late 1990s. Mom couldn’t see it at the time, but she was an integral part of what was to become an enormous change in our culture–a change that is still in process today.

After my father’s premature death in late 1976, Mom moved to Los Angeles to be near her two younger daughters. For the remainder of her life, she continued to fulfill her personal commitment to share the vast knowledge and experience she had gained from her rich history in the organic foods movement.